Southeast AsiaMay 29, 2010 Unmasked: Thailand's men in blackBy Kenneth Todd Ruiz and Olivier Sarbil

BANGKOK - A cigarette hanging from his lips, a sinewy man with a knotted-up beard perched on the back of a plastic chair and spoke into a military-grade radio.

''Happy birthday," he said in English. Moments later a sonorous detonation boomed from afar in the heart of the Thai capital. A cluster of anti-government protesters crowded around him exulted, shouting ''Happy birthday'' in unison. Many more such coded celebrations would follow in the next 24 hours.

It's five days before the army would send armored personnel carriers into central Bangkok on May 19 to decisively quash the

''red shirt'' occupation, and your correspondents are inside a tent with the infamous paramilitaries, dubbed ''men in black'' by the media, as they prepared for war.

They let us inside their secret world on one condition: if we took any pictures, they would kill us.

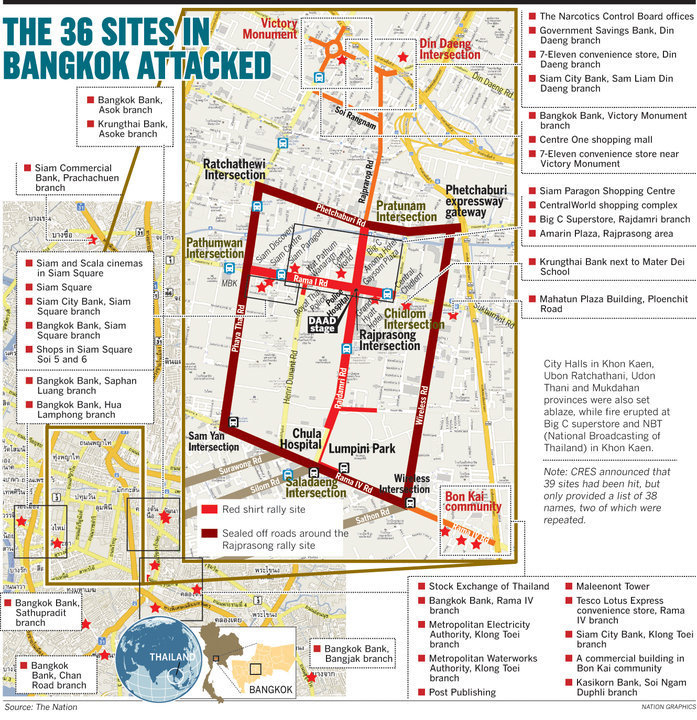

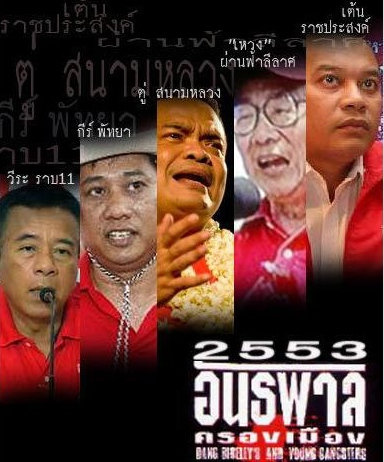

These were not the regular black-attired security guards employed by the United Front for Democracy against Dictatorship, or UDD, anti-government protest group who generally didn't carry guns. These were the secretive and heavily armed agent provocateurs whose connections, by their own admission, run to the top of the UDD, also known as the red shirts.

Several UDD co-leaders have since been detained and branded as ''terrorists'' by the Thai government. On Wednesday, Thai authorities issued an arrest warrant for self-exiled former prime minister Thaksin Shinawatra on terrorism charges, alleging a link between the fugitive politician and the UDD gunmen's violent campaign. Thaksin swiftly denied the charges.

There was a simple honesty to our arrangement with the fighters, but their death threat didn't preclude Thai-style hospitality. Only one man voiced displeasure with our presence; he asked his comrades about us, but he used the Thai pronoun for ''it''.

As the sun set on May 14 behind the UDD's bamboo-and-tire fortress erected in the heart of one of Bangkok's top commercial districts, the men ate hot noodles and whispered anxiously about army shooters. Snipers angered them.

Twenty-four hours earlier, Bangkok had been plunged into chaos after the man whom they said issued their orders directly, renegade army officer Maj Gen Khattiya Sawasdipol, was struck down and eventually died from a sniper's bullet as he spoke to a reporter. The government has denied responsibility for the hit.

Khattiya, a celebrity rogue revered by many red shirts, often spoke fondly of what he called the ''Ronin Warriors'' - Ronin being samurai with no lord or master. In February, he boasted to reporters of training an undisclosed number of former military men to defend the red shirts, but later publicly denied leading them.

Absent Khattiya's leadership, discipline inside the red fortress was on the decline. Alcohol flowed freely, fueling tempers and fist-fights. Earlier in the day a Ronin fighter fired an Israeli-made TAR-21 assault rifle, seized from the army in April, at an army helicopter overhead.

Competing personalities vied for dominance among the disordered Ronin, but the bearded man who spoke little was calling the shots for now. "Do you know who is in charge here?" he said. "It's me."

At least until another unnamed commandant he described as second to Khattiya arrived to assume command and investigate why journalists were with the gunmen.

''Not Terrorists Not Violent; Only Peaceful and Democracy,'' read a banner hanging outside the barrier of jumbled tires. Inside, it was an open secret who the gunmen were; no less secret were the perimeter bombs, connected by dirty gray cables, designed to inflict heavy casualties on any advancing government army soldiers.

Some of the men held their firearms tightly concealed under jackets. Just after sunset, oblong packages wrapped in black plastic were carried into tents in Lumpini Park from elsewhere in the camp. Running at a crouch, we were moved to a different tent nearer the memorial statue of Thai King Rama VI. The Ronin moved between tents often in this way to avoid detection from government snipers.

Twenty-seven men crouched in darkness inside the tent. Newspapers covered any illuminated displays from radios or other electronics, and we were asked to turn off our cell phones. One gunman suggested army snipers would kill them all at first light if they had the chance.

''Don't worry; safe. Thai-style,'' their combat medic said to us in English, gesturing to layers of tarps obscuring the ground from potential snipers where we were camped with them.

Fewer than half were paramilitaries, the rest regular black-shirts providing support and catering to the gunmen's needs. Some ran errands, others fetched water, coffee and M-150 energy drinks. The Ronin were structured like a military unit, complete with a radioman and the combat medic. They apparently had had training in explosives and munitions, which they put to use in handling plastic explosives and planting bombs for remote-detonation along the camp's edge.

Despite media speculation that the Ronin were comprised of former anti-communist commandos, most of the men we met were much too young, looking to be in their early 20s. Many had been paratroopers and one said he came from the navy. Most originated from the same upcountry, rice-basket provinces the majority of red shirts called home. Several said they were still active-duty soldiers.

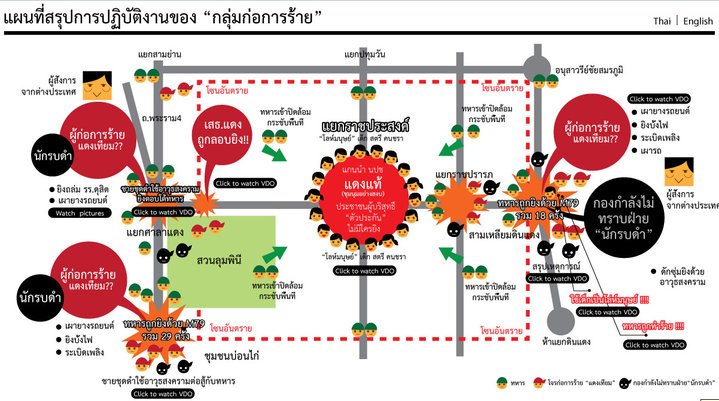

Eventually a call came in from a UDD guard. The army had succeeded in securing a location near Pratunam, the intersection bounding the northern extent of the red-occupied commercial district, and was pushing hard against protesters. They needed help.

M16 and AR-15 rifles slid free from concealment under plastic or inside their clothing. In less than 10 minutes, the gunmen loaded ammunition into clips and locked them into place.

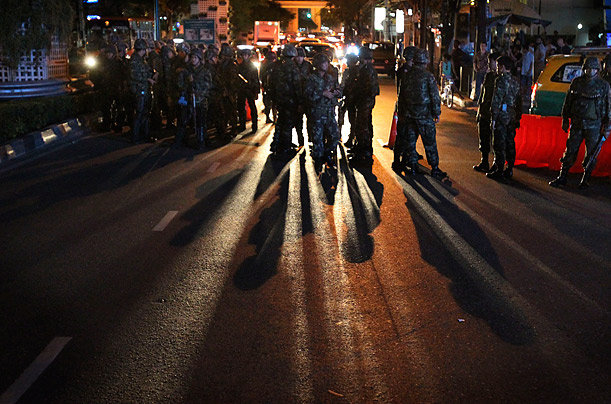

Ammunition was running low, they said. Each fighter was given no more than 30 rounds to carry. Although we didn't see any M79 grenade launchers, the Ronin discussed a bulky sack of grenades they were carrying. Just after 9 pm, the dozen fighters rose and scurried silently into the night to sow another round of mayhem.

For the next nine hours, bursts of intense gunfire erupted from areas around the red-zone perimeter. first from the direction of Pratunam, later from points along Rama IV Road.

Their tactics were consistent with those of trained guerrillas and snipers, letting off brief fusillades of gunfire before repositioning. They terrorized regular Thai army soldiers throughout the night, winding them up and denying them sleep.

At 6 am on May 16, they swaggered back into the camp under covering fire from homemade rockets to the cheers of the assembled reds. Visibly weary but beaming triumphant smiles, the men shouldered the night's spoils - body armor, riot shields, batons, helmets, flashlights and other gear taken from Thai security forces - some of which they handed out as gifts.

If the battle for Bangkok was largely a hearts-and-minds campaign for public support, the Ronin's actions undermined the nonviolent ethos espoused by the UDD.

They described their purpose as ''protecting'' the demonstrators and standing as a force-equalizer against Thai security forces. They perceived themselves as ''black angels'' watching over the unarmed farmers and families who comprised the red shirt rank and file.

Despite this heroic self-image, these angels brought death and chaos. Their campaign of violence is believed to have claimed a number of innocent lives and possibly provoked the deaths of dozens more.

Prime Minister Abhisit Vejjajiva and his government, along with other observers, blame them for tipping an already tense stand-off on April 10 into bloody pandemonium by killing army officers and attacking soldiers, who then fired live rounds into red shirt crowds. Twenty-five people died that day.

''Soldiers are lining up with their war weapons and shooting into crowds of red shirts, all of whom are completely unarmed,'' UDD spokesman Sean Boonpracong said from the Ratchaprasong stage on May 15, only hours after the Ronin returned from their mission.

Their actions also handed the civilian government the excuse it needed to send in troops with deadly purpose on May 19 to end the UDD's six-week occupation of Ratchaprasong. Seeking to justify the government's use of lethal force, Deputy Prime Minister Suthep Thaugsuban revealed seized weaponry before foreign diplomats and the press on May 22.

"Terrorists have used these weapons to attack officials and innocent people," he said.

Earlier this month, Abhisit branded their now deceased chief, Khattiya, a ''terrorist'' ringleader. Before he was shot, Khattiya, a larger-than-life character given to brash claims and with an uncanny ability to predict unclaimed grenade attacks across Bangkok, sometimes made little effort to conceal his role as Ronin commander.

When hundreds of pro-government protestors rallied near the UDD's fortress on April 22, he announced the imminent arrival of ''some men wearing black'' to aid the reds. Soon thereafter, five M79 grenades landed near a pro-government group, killing a 26-year-old woman and injuring nearly 100 others. That weapon, the M79 grenade launcher, is consistent with a months-long campaign of violence and property destruction, which the government has also pinned on the UDD.

In his May 3 comments, Abhisit also linked Khattiya to Thaksin, the fugitive billionaire the UDD aims to return to power. Khattiya's relationship with Thaksin raises the question, as posed by the government's terrorism case, what is the politician's knowledge of the commandos?

He didn't address the question when it was put to him directly in an interview on Wednesday with the Australian Broadcast Corporation. "There is no evidence at all, it's just the allegations," he said. [1]

Khattiya traveled to Dubai to meet Thaksin in March, according to press reports. He also said they spoke by telephone on occasion, most recently on May 3. That was one week before Thaksin is believed to have scuttled a peace plan and Khattiya threatened to seize control of the UDD from its more moderate leadership.

Those leaders were poised to accept Abhisit's five-point ''reconciliation road map'', which included a proposal for early elections in November, and the deal's collapse precipitated the military crackdown. On the day of the crackdown, the Ronin fought the army as they fell back in an organized withdrawal from the red fortress.

Just after 1:30 pm on May 19, these correspondents witnessed two Thai soldiers and a Canadian journalist seriously injured by one of many M79 grenades fired from an elevated position believed to be a nearby Skytrain station. Later, as Central World Plaza mall, was set alight and burned, they engaged in a fierce firefight with the army several blocks away. Then they just disappeared.

It isn't clear why the Ronin raised the veil of secrecy for us, but perhaps it was knowledge that their fight, and possibly their lives, could soon end with the coming military crackdown. That doesn't seem to have happened, however.

Leaders of the UDD may have surrendered to police and their followers have dispersed or been arrested, but the deadly fighters are believed to be loose in the city, ready to fight another day. Thaksin suggested without elaborating after May 19 that angry UDD protestors might resort to ''guerilla'' tactics.

Meanwhile, Bangkok struggles to reclaim a sense of normalcy while the gunmen remain at large. On Monday, Suthep Thaugsuban argued for extending a curfew then in effect, citing fears that an ''underground movement" planning to cause chaos was still loose in the capital.

Note:1. For interview, see

here.

Kenneth Todd Ruiz is a freelance journalist living in Bangkok and blogging at reporterinexile.com. Olivier Sarbil is a Bangkok-based photojournalist whose images of recent events in Thailand are online at OlivierSarbil.com.(Copyright 2010 Asia Times Online (Holdings) Ltd. All rights reserved. Please contact us about republishing.)